FUVEST 2023

Questão 78840

UNESP

(UNESP - 2023)

Para responder às questões de 07 a 10, leia o capítulo CXVII do romance Quincas Borba, de Machado de Assis.

A história do casamento de Maria Benedita é curta; e, posto Sofia a ache vulgar, vale a pena dizê-la. Fique desde já admitido que, se não fosse a epidemia das Alagoas, talvez não chegasse a haver casamento; donde se conclui que as catástrofes são úteis, e até necessárias. Sobejam exemplos; mas basta um contozinho que ouvi em criança, e que aqui lhes dou em duas linhas. Era uma vez uma choupana que ardia na estrada; a dona, — um triste molambo de mulher, — chorava o seu desastre, a poucos passos, sentada no chão. Senão quando, indo a passar um homem ébrio, viu o incêndio, viu a mulher, perguntou-lhe se a casa era dela.

— É minha, sim, meu senhor; é tudo o que eu possuía neste mundo.

— Dá-me então licença que acenda ali o meu charuto?

O padre que me contou isto certamente emendou o texto original; não é preciso estar embriagado para acender um charuto nas misérias alheias. Bom padre Chagas! — Chamava-se Chagas. — Padre mais que bom, que assim me incutiste por muitos anos essa ideia consoladora, de que ninguém, em seu juízo, faz render o mal dos outros; não contando o respeito que aquele bêbado tinha ao princípio da propriedade, — a ponto de não acender o charuto sem pedir licença à dona das ruínas. Tudo ideias consoladoras. Bom padre Chagas!

(Quincas Borba, 2012.)

No capítulo, o estilo adotado pelo narrador caracteriza-se como

Ver questãoQuestão 78841

UNESP

(UNESP - 2023)

Para responder às questões de 07 a 10, leia o capítulo CXVII do romance Quincas Borba, de Machado de Assis.

A história do casamento de Maria Benedita é curta; e, posto Sofia a ache vulgar, vale a pena dizê-la. Fique desde já admitido que, se não fosse a epidemia das Alagoas, talvez não chegasse a haver casamento; donde se conclui que as catástrofes são úteis, e até necessárias. Sobejam exemplos; mas basta um contozinho que ouvi em criança, e que aqui lhes dou em duas linhas. Era uma vez uma choupana que ardia na estrada; a dona, — um triste molambo de mulher, — chorava o seu desastre, a poucos passos, sentada no chão. Senão quando, indo a passar um homem ébrio, viu o incêndio, viu a mulher, perguntou-lhe se a casa era dela.

— É minha, sim, meu senhor; é tudo o que eu possuía neste mundo.

— Dá-me então licença que acenda ali o meu charuto?

O padre que me contou isto certamente emendou o texto original; não é preciso estar embriagado para acender um charuto nas misérias alheias. Bom padre Chagas! — Chamava-se Chagas. — Padre mais que bom, que assim me incutiste por muitos anos essa ideia consoladora, de que ninguém, em seu juízo, faz render o mal dos outros; não contando o respeito que aquele bêbado tinha ao princípio da propriedade, — a ponto de não acender o charuto sem pedir licença à dona das ruínas. Tudo ideias consoladoras. Bom padre Chagas!

(Quincas Borba, 2012.)

No trecho “Sobejam exemplos; mas basta um contozinho que ouvi em criança, e que aqui lhes dou em duas linhas.” (1o parágrafo), a inclusão do leitor na narrativa pode ser constatada pelo termo

Ver questãoQuestão 78842

UNESP

(UNESP - 2023)

Para responder às questões de 07 a 10, leia o capítulo CXVII do romance Quincas Borba, de Machado de Assis.

A história do casamento de Maria Benedita é curta; e, posto Sofia a ache vulgar, vale a pena dizê-la. Fique desde já admitido que, se não fosse a epidemia das Alagoas, talvez não chegasse a haver casamento; donde se conclui que as catástrofes são úteis, e até necessárias. Sobejam exemplos; mas basta um contozinho que ouvi em criança, e que aqui lhes dou em duas linhas. Era uma vez uma choupana que ardia na estrada; a dona, — um triste molambo de mulher, — chorava o seu desastre, a poucos passos, sentada no chão. Senão quando, indo a passar um homem ébrio, viu o incêndio, viu a mulher, perguntou-lhe se a casa era dela.

— É minha, sim, meu senhor; é tudo o que eu possuía neste mundo.

— Dá-me então licença que acenda ali o meu charuto?

O padre que me contou isto certamente emendou o texto original; não é preciso estar embriagado para acender um charuto nas misérias alheias. Bom padre Chagas! — Chamava-se Chagas. — Padre mais que bom, que assim me incutiste por muitos anos essa ideia consoladora, de que ninguém, em seu juízo, faz render o mal dos outros; não contando o respeito que aquele bêbado tinha ao princípio da propriedade, — a ponto de não acender o charuto sem pedir licença à dona das ruínas. Tudo ideias consoladoras. Bom padre Chagas!

(Quincas Borba, 2012.)

“A história do casamento de Maria Benedita é curta; e, posto Sofia a ache vulgar, vale a pena dizê-la.” (1o parágrafo)

No contexto em que se insere, a oração sublinhada expressa ideia de

Ver questãoQuestão 78844

UNESP

(UNESP - 2023)

Para responder às questões 11 e 12, leia alguns trechos do “Prefácio Interessantíssimo” de Pauliceia Desvairada, de Mário de Andrade, obra considerada marco do Modernismo brasileiro e publicada originalmente em julho de 1922.

Leitor:

Está fundado o Desvairismo.

*

Este prefácio, apesar de interessante, inútil.

*

Quando sinto a impulsão lírica escrevo sem pensar tudo o que meu inconsciente me grita. Penso depois: não só para corrigir, como para justificar o que escrevi. Daí a razão deste Prefácio Interessantíssimo.

*

E desculpe-me por estar tão atrasado dos movimentos artísticos atuais. Sou passadista, confesso. Ninguém pode se libertar duma só vez das teorias-avós que bebeu; e o autor deste livro seria hipócrita se pretendesse representar orientação moderna que ainda não compreende bem.

*

Não sou futurista (de Marinetti). Disse e repito-o. Tenho pontos de contato com o futurismo. Oswald de Andrade, chamando-me de futurista, errou. A culpa é minha. Sabia da existência do artigo e deixei que saísse. Tal foi o escândalo, que desejei a morte do mundo. Era vaidoso. Quis sair da obscuridade. Hoje tenho orgulho. Não me pesaria reentrar na obscuridade. Pensei que se discutiriam minhas ideias (que nem são minhas): discutiram minhas intenções.

*

Um pouco de teoria?

Acredito que o lirismo, nascido no subconsciente, acrisolado num pensamento claro ou confuso, cria frases que são versos inteiros, sem prejuízo de medir tantas sílabas, com acentuação determinada.

(Mário de Andrade. Poesias completas, 2013.)

Ao enfatizar o papel do inconsciente na atividade criativa, o “Prefácio Interessantíssimo” expõe uma poética que revela afinidades com a estética

Ver questãoQuestão 78845

UNESP

(UNESP - 2023)

Para responder às questões 11 e 12, leia alguns trechos do “Prefácio Interessantíssimo” de Pauliceia Desvairada, de Mário de Andrade, obra considerada marco do Modernismo brasileiro e publicada originalmente em julho de 1922.

Leitor:

Está fundado o Desvairismo.

*

Este prefácio, apesar de interessante, inútil.

*

Quando sinto a impulsão lírica escrevo sem pensar tudo o que meu inconsciente me grita. Penso depois: não só para corrigir, como para justificar o que escrevi. Daí a razão deste Prefácio Interessantíssimo.

*

E desculpe-me por estar tão atrasado dos movimentos artísticos atuais. Sou passadista, confesso. Ninguém pode se libertar duma só vez das teorias-avós que bebeu; e o autor deste livro seria hipócrita se pretendesse representar orientação moderna que ainda não compreende bem.

*

Não sou futurista (de Marinetti). Disse e repito-o. Tenho pontos de contato com o futurismo. Oswald de Andrade, chamando-me de futurista, errou. A culpa é minha. Sabia da existência do artigo e deixei que saísse. Tal foi o escândalo, que desejei a morte do mundo. Era vaidoso. Quis sair da obscuridade. Hoje tenho orgulho. Não me pesaria reentrar na obscuridade. Pensei que se discutiriam minhas ideias (que nem são minhas): discutiram minhas intenções.

*

Um pouco de teoria?

Acredito que o lirismo, nascido no subconsciente, acrisolado num pensamento claro ou confuso, cria frases que são versos inteiros, sem prejuízo de medir tantas sílabas, com acentuação determinada.

(Mário de Andrade. Poesias completas, 2013.)

Mário de Andrade recorre à metalinguagem no seguinte trecho:

Ver questãoQuestão 78851

UNESP

(UNESP - 2023)

Leia o texto para responder às questões de 13 a 18.

Black authors shake up Brazil’s literary scene

Itamar Vieira Junior, whose day job working for the Brazilian government on land reform took him deep into the impoverished countryside, knew next to nothing about the mainstream publishing industry when he put the final touches on a novel he had been writing on and off for decades. On a whim, in April 2018, he sent the manuscript for Torto Arado, which means crooked plow, to a literary contest in Portugal, wondering what the jury would make of the hardscrabble tale of two sisters in a rural district in northeastern Brazil where the legacy of slavery remains palpable.

To his astonishment, Torto Arado won the 2018 LeYa award, a major Portuguese-language literary prize focused on discovering new voices. The recognition jump-started Mr. Vieira’s career, making him a leading voice among the Black authors who have jolted Brazil’s literary establishment in recent years with imaginative and searing works that have found commercial success and critical acclaim.

Torto Arado was the best-selling book in Brazil in 2021, with more than 300,000 copies sold to date. The previous year, that distinction went to Djamila Ribeiro’s A Little Anti-Racist Handbook (Pequeno Manual Antirracista), a succinct and plainly written dissection of systemic racism in Brazil.

Mr. Vieira, a geographer, and Ms. Ribeiro, who studied philosophy, are part of a generation of Black Brazilians who became the first in their families to get a college degree, taking advantage of Federal Government programs. Mr. Vieira managed to use his day job at Brazil’s land reform agency, where he has worked since 2006, to do field research. He studied the politics and power dynamics that shape the lives of rural workers, including some who toil in conditions analogous to modern-day slavery. That experience, he said, made the characters in his novel more layered and their fictional hometown, Água Negra, which means black water, feel authentic.

The two authors are among the highest profile figures of a literary boom that includes Black contemporary writers and authors who are experiencing a revival. The clearest example is Carolina Maria de Jesus, who died in 1977 and whose memoir, Child of the Dark (Quarto de Despejo), is now a literary sensation, as it was when it was published in 1960. The book, a compilation of diary entries by Ms. Jesus, a single mother of three, offers a raw account of daily life in a São Paulo slum where dwellers picked through garbage for food and slept in shacks patched together with slabs of cardboard.

(Ernesto Londoño. www.nytimes.com, 12.02.2022. Adaptado.)

The aim of the text is to

Ver questãoQuestão 78853

UNESP

(UNESP - 2023)

Leia o texto para responder às questões de 13 a 18.

Black authors shake up Brazil’s literary scene

Itamar Vieira Junior, whose day job working for the Brazilian government on land reform took him deep into the impoverished countryside, knew next to nothing about the mainstream publishing industry when he put the final touches on a novel he had been writing on and off for decades. On a whim, in April 2018, he sent the manuscript for Torto Arado, which means crooked plow, to a literary contest in Portugal, wondering what the jury would make of the hardscrabble tale of two sisters in a rural district in northeastern Brazil where the legacy of slavery remains palpable.

To his astonishment, Torto Arado won the 2018 LeYa award, a major Portuguese-language literary prize focused on discovering new voices. The recognition jump-started Mr. Vieira’s career, making him a leading voice among the Black authors who have jolted Brazil’s literary establishment in recent years with imaginative and searing works that have found commercial success and critical acclaim.

Torto Arado was the best-selling book in Brazil in 2021, with more than 300,000 copies sold to date. The previous year, that distinction went to Djamila Ribeiro’s A Little Anti-Racist Handbook (Pequeno Manual Antirracista), a succinct and plainly written dissection of systemic racism in Brazil.

Mr. Vieira, a geographer, and Ms. Ribeiro, who studied philosophy, are part of a generation of Black Brazilians who became the first in their families to get a college degree, taking advantage of Federal Government programs. Mr. Vieira managed to use his day job at Brazil’s land reform agency, where he has worked since 2006, to do field research. He studied the politics and power dynamics that shape the lives of rural workers, including some who toil in conditions analogous to modern-day slavery. That experience, he said, made the characters in his novel more layered and their fictional hometown, Água Negra, which means black water, feel authentic.

The two authors are among the highest profile figures of a literary boom that includes Black contemporary writers and authors who are experiencing a revival. The clearest example is Carolina Maria de Jesus, who died in 1977 and whose memoir, Child of the Dark (Quarto de Despejo), is now a literary sensation, as it was when it was published in 1960. The book, a compilation of diary entries by Ms. Jesus, a single mother of three, offers a raw account of daily life in a São Paulo slum where dwellers picked through garbage for food and slept in shacks patched together with slabs of cardboard.

(Ernesto Londoño. www.nytimes.com, 12.02.2022. Adaptado.)

According to the text, the novel Torto Arado, by Itamar Vieira Junior,

Ver questãoQuestão 78855

UNESP

(UNESP - 2023)

Leia o texto para responder às questões de 13 a 18.

Black authors shake up Brazil’s literary scene

Itamar Vieira Junior, whose day job working for the Brazilian government on land reform took him deep into the impoverished countryside, knew next to nothing about the mainstream publishing industry when he put the final touches on a novel he had been writing on and off for decades. On a whim, in April 2018, he sent the manuscript for Torto Arado, which means crooked plow, to a literary contest in Portugal, wondering what the jury would make of the hardscrabble tale of two sisters in a rural district in northeastern Brazil where the legacy of slavery remains palpable.

To his astonishment, Torto Arado won the 2018 LeYa award, a major Portuguese-language literary prize focused on discovering new voices. The recognition jump-started Mr. Vieira’s career, making him a leading voice among the Black authors who have jolted Brazil’s literary establishment in recent years with imaginative and searing works that have found commercial success and critical acclaim.

Torto Arado was the best-selling book in Brazil in 2021, with more than 300,000 copies sold to date. The previous year, that distinction went to Djamila Ribeiro’s A Little Anti-Racist Handbook (Pequeno Manual Antirracista), a succinct and plainly written dissection of systemic racism in Brazil.

Mr. Vieira, a geographer, and Ms. Ribeiro, who studied philosophy, are part of a generation of Black Brazilians who became the first in their families to get a college degree, taking advantage of Federal Government programs. Mr. Vieira managed to use his day job at Brazil’s land reform agency, where he has worked since 2006, to do field research. He studied the politics and power dynamics that shape the lives of rural workers, including some who toil in conditions analogous to modern-day slavery. That experience, he said, made the characters in his novel more layered and their fictional hometown, Água Negra, which means black water, feel authentic.

The two authors are among the highest profile figures of a literary boom that includes Black contemporary writers and authors who are experiencing a revival. The clearest example is Carolina Maria de Jesus, who died in 1977 and whose memoir, Child of the Dark (Quarto de Despejo), is now a literary sensation, as it was when it was published in 1960. The book, a compilation of diary entries by Ms. Jesus, a single mother of three, offers a raw account of daily life in a São Paulo slum where dwellers picked through garbage for food and slept in shacks patched together with slabs of cardboard.

(Ernesto Londoño. www.nytimes.com, 12.02.2022. Adaptado.)

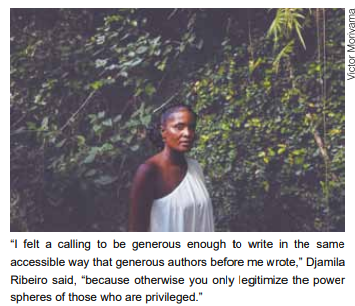

De acordo com a legenda da imagem que retrata Djamila Ribeiro, a escritora

Ver questãoQuestão 78857

UNESP

(UNESP - 2023)

Leia o texto para responder às questões de 13 a 18.

Black authors shake up Brazil’s literary scene

Itamar Vieira Junior, whose day job working for the Brazilian government on land reform took him deep into the impoverished countryside, knew next to nothing about the mainstream publishing industry when he put the final touches on a novel he had been writing on and off for decades. On a whim, in April 2018, he sent the manuscript for Torto Arado, which means crooked plow, to a literary contest in Portugal, wondering what the jury would make of the hardscrabble tale of two sisters in a rural district in northeastern Brazil where the legacy of slavery remains palpable.

To his astonishment, Torto Arado won the 2018 LeYa award, a major Portuguese-language literary prize focused on discovering new voices. The recognition jump-started Mr. Vieira’s career, making him a leading voice among the Black authors who have jolted Brazil’s literary establishment in recent years with imaginative and searing works that have found commercial success and critical acclaim.

Torto Arado was the best-selling book in Brazil in 2021, with more than 300,000 copies sold to date. The previous year, that distinction went to Djamila Ribeiro’s A Little Anti-Racist Handbook (Pequeno Manual Antirracista), a succinct and plainly written dissection of systemic racism in Brazil.

Mr. Vieira, a geographer, and Ms. Ribeiro, who studied philosophy, are part of a generation of Black Brazilians who became the first in their families to get a college degree, taking advantage of Federal Government programs. Mr. Vieira managed to use his day job at Brazil’s land reform agency, where he has worked since 2006, to do field research. He studied the politics and power dynamics that shape the lives of rural workers, including some who toil in conditions analogous to modern-day slavery. That experience, he said, made the characters in his novel more layered and their fictional hometown, Água Negra, which means black water, feel authentic.

The two authors are among the highest profile figures of a literary boom that includes Black contemporary writers and authors who are experiencing a revival. The clearest example is Carolina Maria de Jesus, who died in 1977 and whose memoir, Child of the Dark (Quarto de Despejo), is now a literary sensation, as it was when it was published in 1960. The book, a compilation of diary entries by Ms. Jesus, a single mother of three, offers a raw account of daily life in a São Paulo slum where dwellers picked through garbage for food and slept in shacks patched together with slabs of cardboard.

(Ernesto Londoño. www.nytimes.com, 12.02.2022. Adaptado.)

No trecho da legenda da imagem que retrata Djamila Ribeiro “because otherwise you only legitimize the power spheres of those who are privileged”, o termo sublinhado expressa

Ver questãoQuestão 78861

UNESP

(UNESP - 2023)

Leia o texto para responder às questões de 13 a 18.

Black authors shake up Brazil’s literary scene

Itamar Vieira Junior, whose day job working for the Brazilian government on land reform took him deep into the impoverished countryside, knew next to nothing about the mainstream publishing industry when he put the final touches on a novel he had been writing on and off for decades. On a whim, in April 2018, he sent the manuscript for Torto Arado, which means crooked plow, to a literary contest in Portugal, wondering what the jury would make of the hardscrabble tale of two sisters in a rural district in northeastern Brazil where the legacy of slavery remains palpable.

To his astonishment, Torto Arado won the 2018 LeYa award, a major Portuguese-language literary prize focused on discovering new voices. The recognition jump-started Mr. Vieira’s career, making him a leading voice among the Black authors who have jolted Brazil’s literary establishment in recent years with imaginative and searing works that have found commercial success and critical acclaim.

Torto Arado was the best-selling book in Brazil in 2021, with more than 300,000 copies sold to date. The previous year, that distinction went to Djamila Ribeiro’s A Little Anti-Racist Handbook (Pequeno Manual Antirracista), a succinct and plainly written dissection of systemic racism in Brazil.

Mr. Vieira, a geographer, and Ms. Ribeiro, who studied philosophy, are part of a generation of Black Brazilians who became the first in their families to get a college degree, taking advantage of Federal Government programs. Mr. Vieira managed to use his day job at Brazil’s land reform agency, where he has worked since 2006, to do field research. He studied the politics and power dynamics that shape the lives of rural workers, including some who toil in conditions analogous to modern-day slavery. That experience, he said, made the characters in his novel more layered and their fictional hometown, Água Negra, which means black water, feel authentic.

The two authors are among the highest profile figures of a literary boom that includes Black contemporary writers and authors who are experiencing a revival. The clearest example is Carolina Maria de Jesus, who died in 1977 and whose memoir, Child of the Dark (Quarto de Despejo), is now a literary sensation, as it was when it was published in 1960. The book, a compilation of diary entries by Ms. Jesus, a single mother of three, offers a raw account of daily life in a São Paulo slum where dwellers picked through garbage for food and slept in shacks patched together with slabs of cardboard.

(Ernesto Londoño. www.nytimes.com, 12.02.2022. Adaptado.)

In the excerpt from the fourth paragraph “That experience, he said, made the characters in his novel more layered”, the underlined expression refers to

Ver questão