FUVEST 2021

Questão 66185

UNESP

(UNESP 2021 - 2ª fase)

Observe as imagens e leia o texto.

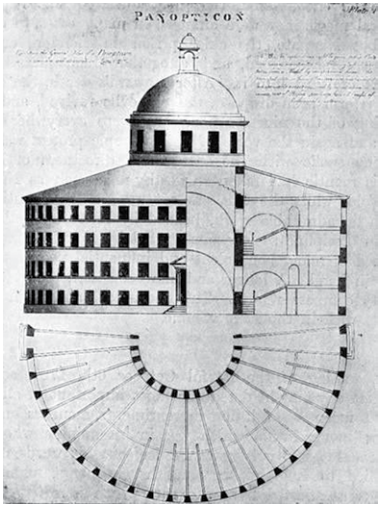

Projeto do panóptico, novo modelo de vigilância, proposto por Jeremy Bentham no final do século XVIII, para ser utilizado em

presídios e outros espaços que exigissem controle rigoroso.

Presídio da Ilha de Pinos, em Cuba, construído no final da década de 1920, a partir do modelo do panóptico, e hoje abandonado.

(https://medium.com)

O princípio é: na periferia, uma construção em anel; no centro, uma torre; esta possui grandes janelas que se abrem para a parte interior do anel. A construção periférica é dividida em celas, cada uma ocupando toda a largura da construção. Estas celas têm duas janelas: uma abrindo-se para o interior, correspondendo às janelas da torre; outra, dando para o exterior, permite que a luz atravesse a cela de um lado a outro. Basta então colocar um vigia na torre central e em cada cela trancafiar um louco, um doente, um condenado, um operário ou um estudante. Devido ao efeito de contraluz, pode-se perceber da torre, recortando-se na luminosidade, as pequenas silhuetas prisioneiras nas celas da periferia. Em suma, inverte-se o princípio da masmorra; a luz e o olhar de um vigia captam melhor que o escuro que, no fundo, protegia. […]

As mudanças econômicas do século XVIII tornaram necessário fazer circular os efeitos do poder por canais cada vez mais sutis, chegando até os próprios indivíduos, seus corpos, seus gestos, cada um de seus desempenhos cotidianos. Que o poder, mesmo tendo uma multiplicidade de homens a gerir, seja tão eficaz quanto se ele se exercesse sobre um só. […] Bentham […] coloca o problema da visibilidade, mas pensando em uma visibilidade organizada inteiramente em torno de um olhar dominador e vigilante. Ele faz funcionar o projeto de uma visibilidade universal, que agiria em proveito de um poder rigoroso e meticuloso.

(Michel Foucault. Microfísica do poder, 1979.)

O projeto do panóptico de Bentham associou-se, na origem,

Ver questãoQuestão 66186

UNESP

(UNESP - 2021 - 2ª FASE)

Leia o texto para responder a questão.

“Culture is language”:

why an indigenous tongue is thriving in Paraguay

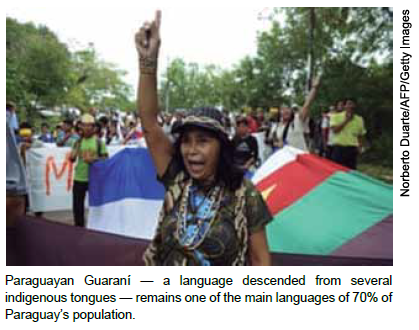

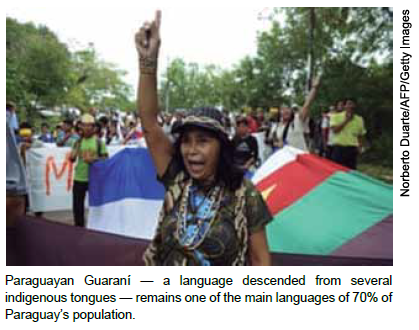

On a hillside monument in Asunción, a statue of the mythologized indigenous chief Lambaré stands alongside other great leaders from Paraguayan history. The other historical heroes on display are of mixed ancestry, but the idea of a noble indigenous heritage is strong in Paraguay, and — uniquely in the Americas — can be expressed by most of the country’s people in an indigenous language: Paraguayan Guaraní. “Guaraní is our culture — it’s where our roots are,” said Tomasa Cabral, a market vendor in the city.

Elsewhere in the Americas, European colonial languages are pushing native languages towards extinction, but Paraguayan Guaraní — a language descended from several indigenous tongues — remains one of the main languages of 70% of the country’s population. And unlike other widely spoken native tongues — such as Quechua, Aymara or the Mayan languages — it is overwhelmingly spoken by non-indigenous people.

Miguel Verón, a linguist and member of the Academy of the Guaraní Language, said the language had survived partly because of the landlocked country’s geographic isolation and partly because of the “linguistic loyalty” of its people. “The indigenous people refused to learn Spanish,” he said. “The imperial governors had to learn to speak Guaraní.” But while it remains under pressure from Spanish, Paraguayan Guaraní is itself part of the threat looming over the country’s other indigenous languages. Paraguay’s 19 surviving indigenous groups each have their own tongue, but six of them are listed by Unesco as severely or critically endangered.

The benefits of speaking the country’s two official languages were clear. Spanish remains the language of government, and Paraguayan Guaraní is widely spoken in rural areas, where it is a key requisite for many jobs. But the value of maintaining other tongues was incalculable, said Alba Eiragi Duarte, a poet from the Ava Guaraní people. “Our culture is transmitted through our own language: culture is language. When we love our language, we love ourselves.”

(William Costa. www.theguardian.com, 03.09.2020. Adaptado.)

According to the text, the fact that 70% of Paraguayan population speak Guaraní makes the language

Ver questãoQuestão 66187

UNESP

(UNESP - 2021 - 2ª FASE)

Leia o texto para responder a questão.

“Culture is language”:

why an indigenous tongue is thriving in Paraguay

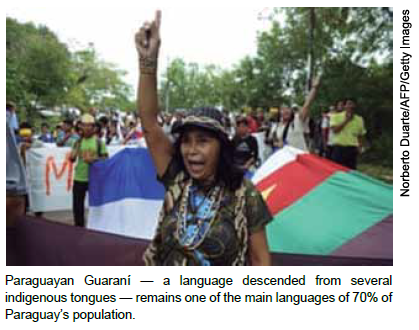

On a hillside monument in Asunción, a statue of the mythologized indigenous chief Lambaré stands alongside other great leaders from Paraguayan history. The other historical heroes on display are of mixed ancestry, but the idea of a noble indigenous heritage is strong in Paraguay, and — uniquely in the Americas — can be expressed by most of the country’s people in an indigenous language: Paraguayan Guaraní. “Guaraní is our culture — it’s where our roots are,” said Tomasa Cabral, a market vendor in the city.

Elsewhere in the Americas, European colonial languages are pushing native languages towards extinction, but Paraguayan Guaraní — a language descended from several indigenous tongues — remains one of the main languages of 70% of the country’s population. And unlike other widely spoken native tongues — such as Quechua, Aymara or the Mayan languages — it is overwhelmingly spoken by non-indigenous people.

Miguel Verón, a linguist and member of the Academy of the Guaraní Language, said the language had survived partly because of the landlocked country’s geographic isolation and partly because of the “linguistic loyalty” of its people. “The indigenous people refused to learn Spanish,” he said. “The imperial governors had to learn to speak Guaraní.” But while it remains under pressure from Spanish, Paraguayan Guaraní is itself part of the threat looming over the country’s other indigenous languages. Paraguay’s 19 surviving indigenous groups each have their own tongue, but six of them are listed by Unesco as severely or critically endangered.

The benefits of speaking the country’s two official languages were clear. Spanish remains the language of government, and Paraguayan Guaraní is widely spoken in rural areas, where it is a key requisite for many jobs. But the value of maintaining other tongues was incalculable, said Alba Eiragi Duarte, a poet from the Ava Guaraní people. “Our culture is transmitted through our own language: culture is language. When we love our language, we love ourselves.”

(William Costa. www.theguardian.com, 03.09.2020. Adaptado.)

No trecho do segundo parágrafo “And unlike other widely spoken native tongues”, o termo sublinhado expressa

Ver questãoQuestão 66188

UNESP

(UNESP - 2021 - 2ª FASE)

Leia o texto para responder a questão.

“Culture is language”:

why an indigenous tongue is thriving in Paraguay

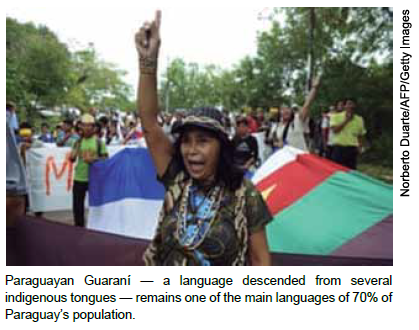

On a hillside monument in Asunción, a statue of the mythologized indigenous chief Lambaré stands alongside other great leaders from Paraguayan history. The other historical heroes on display are of mixed ancestry, but the idea of a noble indigenous heritage is strong in Paraguay, and — uniquely in the Americas — can be expressed by most of the country’s people in an indigenous language: Paraguayan Guaraní. “Guaraní is our culture — it’s where our roots are,” said Tomasa Cabral, a market vendor in the city.

Elsewhere in the Americas, European colonial languages are pushing native languages towards extinction, but Paraguayan Guaraní — a language descended from several indigenous tongues — remains one of the main languages of 70% of the country’s population. And unlike other widely spoken native tongues — such as Quechua, Aymara or the Mayan languages — it is overwhelmingly spoken by non-indigenous people.

Miguel Verón, a linguist and member of the Academy of the Guaraní Language, said the language had survived partly because of the landlocked country’s geographic isolation and partly because of the “linguistic loyalty” of its people. “The indigenous people refused to learn Spanish,” he said. “The imperial governors had to learn to speak Guaraní.” But while it remains under pressure from Spanish, Paraguayan Guaraní is itself part of the threat looming over the country’s other indigenous languages. Paraguay’s 19 surviving indigenous groups each have their own tongue, but six of them are listed by Unesco as severely or critically endangered.

The benefits of speaking the country’s two official languages were clear. Spanish remains the language of government, and Paraguayan Guaraní is widely spoken in rural areas, where it is a key requisite for many jobs. But the value of maintaining other tongues was incalculable, said Alba Eiragi Duarte, a poet from the Ava Guaraní people. “Our culture is transmitted through our own language: culture is language. When we love our language, we love ourselves.”

(William Costa. www.theguardian.com, 03.09.2020. Adaptado.)

De acordo com o texto, um dos motivos da popularidade da língua guarani no Paraguai deve-se

Ver questãoQuestão 66189

UNESP

(UNESP 2021 - 2ª fase)

As revoluções inglesas do século XVII são consideradas, por alguns historiadores, as primeiras revoluções burguesas, pois

Ver questãoQuestão 66190

UNESP

(UNESP 2021 - 2ª fase)

A glorificação da guerra e do heroísmo já era tema constante na literatura nacionalista […]; os escritores nazistas só vieram repetir os clichês já surrados de exaltação dos valores militares, do sacrifício, da força da guerra como fator de soerguimento do orgulho nacional. […] Para o nazismo, a guerra era o cume de uma decisão de cuja verdade não se poderia escapar. Sabiam que tudo estava sendo jogado nela.

(Alcir Lenharo. Nazismo: o triunfo da vontade, 1986.)

No contexto histórico descrito,

Ver questãoQuestão 66191

UNESP

(UNESP - 2021 - 2ª FASE)

Leia o texto para responder a questão.

“Culture is language”:

why an indigenous tongue is thriving in Paraguay

On a hillside monument in Asunción, a statue of the mythologized indigenous chief Lambaré stands alongside other great leaders from Paraguayan history. The other historical heroes on display are of mixed ancestry, but the idea of a noble indigenous heritage is strong in Paraguay, and — uniquely in the Americas — can be expressed by most of the country’s people in an indigenous language: Paraguayan Guaraní. “Guaraní is our culture — it’s where our roots are,” said Tomasa Cabral, a market vendor in the city.

Elsewhere in the Americas, European colonial languages are pushing native languages towards extinction, but Paraguayan Guaraní — a language descended from several indigenous tongues — remains one of the main languages of 70% of the country’s population. And unlike other widely spoken native tongues — such as Quechua, Aymara or the Mayan languages — it is overwhelmingly spoken by non-indigenous people.

Miguel Verón, a linguist and member of the Academy of the Guaraní Language, said the language had survived partly because of the landlocked country’s geographic isolation and partly because of the “linguistic loyalty” of its people. “The indigenous people refused to learn Spanish,” he said. “The imperial governors had to learn to speak Guaraní.” But while it remains under pressure from Spanish, Paraguayan Guaraní is itself part of the threat looming over the country’s other indigenous languages. Paraguay’s 19 surviving indigenous groups each have their own tongue, but six of them are listed by Unesco as severely or critically endangered.

The benefits of speaking the country’s two official languages were clear. Spanish remains the language of government, and Paraguayan Guaraní is widely spoken in rural areas, where it is a key requisite for many jobs. But the value of maintaining other tongues was incalculable, said Alba Eiragi Duarte, a poet from the Ava Guaraní people. “Our culture is transmitted through our own language: culture is language. When we love our language, we love ourselves.”

(William Costa. www.theguardian.com, 03.09.2020. Adaptado.)

The excerpt from the third paragraph “But while it remains under pressure from Spanish, Paraguayan Guaraní is itself part of the threat looming over the country’s other indigenous languages” means that Paraguayan Guaraní

Ver questãoQuestão 66192

UNESP

(UNESP 2021 - 2ª fase)

Observe a charge de Ziraldo, originalmente publicada em 1968.

(Renato Lemos (org.)

Uma história do Brasil através da caricatura: 1840-2006, 2006.)

O diálogo entre o elefante e as cobras, associado à decretação do Ato Institucional número 5, sugere

Ver questãoQuestão 66193

UNESP

(UNESP - 2021 - 2ª FASE)

Leia o texto e examine o mapa.

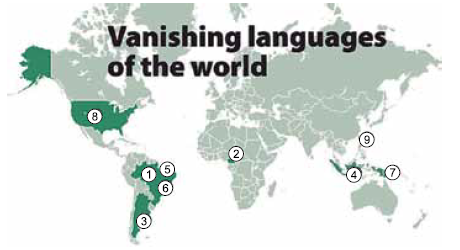

The UN Atlas of Endangered Languages lists 18 languages with only one remaining speaker in 2010. With about one language disappearing every two weeks, some of these have probably already died off.

1. Apiaka is spoken by the indigenous people of the same name who live in the northern state of Mato Grosso in Brazil. The critically endangered language belongs to the Tupi language family. As of 2007, there was one remaining speaker.

2. Bikya is spoken in the North-West Region of Cameroon, in western Africa. The last record of a speaker was in 1986, meaning the language could now be extinct.

3. Chana is spoken in Parana, the capital Argentina’s province of Entre Rios. As of 2008, there was only one speaker.

4. Dampal is spoken in Indonesia, near Bangkir. Unesco reported that there was one speaker as of 2000.

5. Diahoi is spoken in Brazil. Those who speak it live on the indigenous lands Diahui, Middle Madeira river, Southern Amazonas State, Municipality of Humaita. As of 2006, there was one speaker left.

6. Kaixana is a language of Brazil. As of 2008, the sole remaining speaker was believed to be 78-year-old Raimundo Avelino, who lives in Limoeiro in the Japura municipality in the state of Amazonas.

7. Laua is spoken in the Central Province of Papua New Guinea. It is part of the Mailuan language group and is nearly extinct, with one speaker documented in 2000.

8. Patwin is a Native American language spoken in the western US. Descendants live outside San Francisco in Cortina and Colusa, California. There was one fluent speaker documented as of 1997.

9. Pazeh is spoken by Taiwan’s indigenous tribe of the same name. Mrs. Pan Jin Yu, 95, was the sole known speaker as of 2008.

(www.csmonitor.com. Adaptado.)

De acordo com o texto e o mapa,

Ver questãoQuestão 66194

UNESP

(UNESP 2021 - 2ª fase)

Quando se consideram para análise os lugares onde realizamos atividades corriqueiras, banais, do dia a dia, com os quais temos intimidade, as zonas de sombra do objeto não se revelam com facilidade, porque a própria evidência do aparente seduz tanto que obscurece nossa leitura, nosso entendimento do que está oculto, daquilo que é da mais profunda essência do objeto. Na sociedade urbanizada, os lugares onde se realizam as trocas de mercadorias parecem, hoje, especialmente afeitos a refletir luzes que, embora não ceguem, podem impedir-nos de ver com clareza do que realmente se trata.

(Silvana Maria Pintaudi. “O consumo do espaço de consumo”.

In: Márcio Piñon de Oliveira et al (orgs.).O Brasil,

a América Latina e o mundo, 2008.)

As intencionalidades dos objetos e os espaços de consumo tratados no excerto se relacionam, dentre outros fatores, com

Ver questão