FUVEST 2014

Questão 64302

UDESC

(Udesc 2014) Analise as proposições sobre Israel e Palestina.

I. O conflito entre Israel e Palestina começou no século XX, quando os judeus começaram a comprar terras na Palestina. Na década de 30, milhares de judeus já viviam nesta região.

II. O primeiro confronto armado entre Israel e Palestina aconteceu em 1967, o que se convencionou chamar de Guerra dos Sete Dias.

III. A mais importante tentativa de paz entre Israel e Palestina, durante o século XX, aconteceu em 1993. O acordo foi assinado entre Yasser Arafat, líder da OLP (Organização para a Libertação da Palestina), e o primeiro ministro de Israel, Yitzhak Rabin.

IV. Em 2000, nova tentativa de paz foi negociada pelos EUA, sem sucesso, dando início à segunda intifada, o levante armado palestino.

Assinale a alternativa correta.

Ver questãoQuestão 64367

FGV

(FGV)

No Brasil há a presença de variados biomas e ecossistemas ricos em espécies animais, vegetais e micro-organismos. É o país com maior diversidade de anfíbios do mundo: 516 espécies. Possui 522 espécies de mamíferos, das quais 68 são endêmicas; 468 espécies de répteis, das quais 172 são endêmicas, e 1622 espécies de aves (uma em cada seis espécies de aves do mundo ocorre no Brasil).

Adaptado de Conhecer para conservar: As Unidades de Conservação do Estado de São Paulo.

Secretaria do Meio Ambiente do Estado de São Paulo. 1999, p. 66.

Essas informações sobre a biogeografia do território brasileiro permitem concluir:

Questão 64454

ACAFE

(ACAFE)

Biomas são extensões de terra que se encontram sob condições climáticas semelhantes e formam associações distintas de plantas e animais.

Sobre a distribuição e características dos principais biomas terrestres, a alternativa correta é:

Questão 64459

PUC

(PUC/RJ)

As florestas tropicais estão entre os ecossistemas terrestres com maior produtividade primária líquida, o que ocorre em função de maior:

I. intensidade de luz, de temperatura e de chuvas

II. proximidade com o equador

III. área de distribuição na Terra

IV. riqueza do solo

É correto o que se afirma em

Questão 64701

UECE

(UECE - 2014)

TEXT

BRASÍLIA — Brazil’s highest court has long viewed itself as a bastion of manners and formality. Justices call one another “Your Excellency,” dress in billowing robes and wrap each utterance in grandiloquence, as if little had changed from the era when marquises and dukes held sway from their vast plantations.

In one televised feud, Mr. Barbosa questioned another justice about whether he would even be on the court had he not been appointed by his cousin, aformer president impeached in 1992. With another justice, Mr. Barbosa rebuked him over what the chief justice considered his condescending tone, telling him he was not his “capanga,” a term describing a hired thug.

In one of his most scathing comments, Mr. Barbosa, the high court’s first and only black justice, took on the entire legal system of Brazil — where it is still remarkably rare for politicians to ever spend time in prison, even after being convicted of crimes — contending that the mentality of judges was “conservative, pro-status-quo and pro-impunity.”

“I have a temperament that doesn’t adapt well to politics,” Mr. Barbosa, 58, said in a recent interview in his quarters here in the Supreme Federal Tribunal, a modernist landmark designed by the architect Oscar Niemeyer. “It’s because I speak my mind so much.”

His acknowledged lack of tact notwithstanding, he is the driving force behind a series of socially liberal and establishment-shaking rulings, turning Brazil’s highest court — and him in particular — into a newfound political power and the subject of popular fascination.

The court’s recent rulings include a unanimous decision upholding the University of Brasília’s admissions policies aimed at increasing the number of black and indigenous students, opening the way for one of the Western Hemisphere’s most sweeping affirmative action laws for higher education.

In another move, Mr. Barbosa used his sway as chief justice and president of the panel overseeing Brazil’s judiciary to effectively legalize same-sex marriage across the country. And in an anticorruption crusade, he is overseeing the precedent-setting trial of senior political figures in the governing Workers Party for their roles in a vast vote-buying scheme.

Ascending to Brazil’s high court, much less pushing the institution to assert its independence, long seemed out of reach for Mr. Barbosa, the eldest of eight children raised in Paracatu, an impoverished city in Minas Gerais State, where his father worked as a bricklayer.

But his prominence — not just on the court, but in the streets as well — is so well established that masks with his face were sold for Carnival, amateur musicians have composed songs about his handling of the corruption trial and posted them on YouTube, and demonstrators during the huge street protests that shook the nation this year told pollsters that Mr. Barbosa was one of their top choices for president in next year’s elections.

While the protests have subsided since their height in June, the political tumult they set off persists. The race for president, once considered a shoo-in for the incumbent, Dilma Rousseff, is now up in the air, with Mr. Barbosa — who is now so much in the public eye that gossip columnists are following his romance with a woman in her 20s — repeatedly saying he will not run. “I’m not a candidate for anything,” he says.

But the same public glare that has turned him into a celebrity has singed him as well. While he has won widespread admiration for his guidance of the high court, Mr. Barbosa, like almost every other prominent political figure in Brazil, has recently come under scrutiny. And for someone accustomed to criticizing the so-called supersalaries awarded to some members of Brazil’s legal system, the revelations have put Mr. Barbosa on the defensive.

One report in the Brazilian news media described how he received about $180,000 in payments for untaken leaves of absence during his 19 years as a public prosecutor. (Such payments are common in some areas of Brazil’s large public bureaucracy.) Another noted that he bought an apartment in Miami through a limited liability company, suggesting an effort to pay less taxes on the property. In statements, Mr. Barbosa contends that he has done nothing wrong.

In a country where a majority of people now define themselves as black or of mixed race — but where blacks remain remarkably rare in the highest echelons of political institutions and corporations — Mr. Barbosa’s trajectory and abrupt manner have elicited both widespread admiration and a fair amount of resistance.

As a teenager, Mr. Barbosa moved to the capital, Brasília, finding work as a janitor in a courtroom. Against the odds, he got into the University of Brasília, the only black student in its law program at the time. Wanting to see the world, he later won admission into Brazil’s diplomatic service, which promptly sent him to Helsinki, the Finnish capital on the shore of the Baltic Sea.

Sensing that he would not advance much in the diplomatic service, which he has called “one of the most discriminatory institutions of Brazil,” Mr. Barbosa opted for a career as a prosecutor. He alternated between legal investigations in Brazil and studies abroad, gaining fluency in English, French and German, and earning a doctorate in law at Pantheon-Assas University in Paris.

Fascinated by the legal systems of other countries, Mr. Barbosa wrote a book on affirmative action in the United States. He still voices his admiration for figures like Thurgood Marshall, the first black Supreme Court justice in the United States, and William J. Brennan Jr., who for years embodied the court’s liberal vision, clearly drawing inspiration from them as he pushed Brazil’s high court toward socially liberal rulings.

Still, no decision has thrust Mr. Barbosa into Brazil’s public imagination as much as his handling of the trial of political operatives, legislators and bankers found guilty in a labyrinthine corruption scandal called the mensalão, or big monthly allowance, after the regular payments made to lawmakers in exchange for their votes.

Last November, at Mr. Barbosa’s urging, the high court sentenced some of the most powerful figures in the governing Workers Party to years in prison for their crimes in the scheme, including bribery and unlawful conspiracy, jolting a political system in which impunity for politicians has been the norm.

Now the mensalão trial is entering what could be its final phases, and Mr. Barbosa has at times been visibly exasperated that defendants who have already been found guilty and sentenced have managed to avoid hard jail time. He has clashed with other justices over their consideration of a rare legal procedure in which appeals over close votes at the high court are examined.

Losing his patience with one prominent justice, Ricardo Lewandowski, who tried to absolve some defendants of certain crimes, Mr. Barbosa publicly accused him this month of “chicanery” by using legalese to prop up certain positions. An outcry ensued among some who could not stomach Mr. Barbosa’s talking to a fellow justice like that. “Who does Justice Joaquim Barbosa think he is?” asked Ricardo Noblat, a columnist for the newspaper O Globo, questioning whether Mr. Barbosa was qualified to preside over the court. “What powers does he think he has just because he’s sitting in the chair of the chief justice of the Supreme Federal Tribunal?”

Mr. Barbosa did not apologize. In the interview, he said some tension was necessary for the court to function properly. “It was always like this,” he said, contending that arguments are now just easier to see because the court’s proceedings are televised.

Linking the court’s work to the recent wave of protests, he explained that he strongly disagreed with the violence of some demonstrators, but he also said he believed that the street movements were “a sign of democracy’s exuberance.”

“People don’t want to passively stand by and observe these arrangements of the elite, which were always the Brazilian tradition,” he said.

In the sentence "Wanting to see the world, he later won admission into Brazil's diplomatic service", the underlined phrase can be correctly rewritten as

Ver questãoQuestão 64777

UDESC

(UDESC 2014)

O tricloreto de fósforo (PCl3) é um líquido incolor bastante tóxico com larga aplicação industrial, principalmente na fabricação de defensivos agrícolas. A respeito deste composto é correto afirmar que:

Ver questãoQuestão 64847

UNIMONTES

(UNIMONTES - 2014)

Mito de la Pachamama

El Dios del Cielo, Pachacamac, esposo de la Tierra, Pachamama, engendró de dos hijos gemelos; varón y mujer, llamados Wilcas. El Dios Pachacamac murió ahogado en el mar y se encantó en una isla. La Diosa Pachamama sufrió con sus dos hijitos muchas penurias: fue devorada por Warón, el genio maligno que luego, engañado por los mellizos, muere despeñado. Su muerte fue seguida de un espantoso terremoto.

[5] Los mellizos treparon al cielo por una soga, allí los esperaba el Gran Dios Pachacamac. El Wilca Varón se transformó en Sol y la Mujer en Luna, sin que termine la vida de peregrinación que llevaron en la tierra. La diosa Pachamama quedó encantada en un cerro. Pacahacamac la premió por su fidelidad con el Don de la Fecundidad Generadora. Desde entonces desde la cumbre, ella envía sus favores. A través de ella, el Dios del Cielo envía lluvias, fertiliza las tierras y hace que broten las plantas. Y por ello los animales [10] nacen y crecen. […] los Wilcas, transformados en el Sol y la Luna, triunfó la Luz y fue vencido por siempre Walcón, el Dios de la Noche. […] De Pachamama no hay imágenes, no ha cambiado su nombre, tampoco sus funciones, hasta la forma de redirle culto parece mantenerse. A la Madre Tierra se le ofrece toda la cosecha y el primer trago en [15] las fiestas. Todo el mes de Agosto se la invoca, chayando las casas, en las señaladas se le ofrece coca, alcohol y las puntas de las orejas del ganado para pedir su producción. […]

Adaptado de: www. Ecured.cu/index.php/Pachamama ( 31/8/2014).

*os números entre colchetes indicam os números das linhas do texto original.

Em todas as sentenças abaixo, indicou-se corretamente o tempo verbal, EXCETO

Ver questãoQuestão 64852

UDESC

(UDESC - 2014/2)

Obstáculos

[1] Voy andando por un sendero.

Dejo que mis pies me lleven.

Mis ojos se posan en los árboles, en los pájaros, en las piedras. En el horizonte se recorta la silueta de una ciudad. Agudizo la mirada para distinguirla bien. Siento que la [5] ciudad me atrae.

Sin saber cómo, me doy cuenta de que en esta ciudad puedo encontrar todo lo que deseo. Todas mis metas, mis objetivos y mis logros. Mis ambiciones y mis sueños están en esta ciudad. Lo que quiero conseguir, lo que necesito, lo que más me gustaría ser, [10] aquello a lo cual aspiro, o que intento, por lo que trabajo, lo que siempre ambicioné, aquello que sería el mayor de mis éxitos.

Me imagino que todo eso está en esa ciudad. Sin dudar, empiezo a caminar hacia ella. A poco de andar, el sendero se hace cuesta arriba. Me canso un poco, pero no me importa. Sigo. Diviso una sombra negra, más adelante, en el camino. Al acercarme, veo que una]enorme zanja me impide mi paso. Temo… dudo. [15] Me enoja que mi meta no pueda conseguirse fácilmente. De todas maneras decido saltar la zanja. Retrocedo, tomo impulso y salto… Consigo pasarla. Me repongo y sigo caminando.

Unos metros más adelante, aparece otra zanja. Vuelvo a tomar carrera y también la salto. Corro hacia la ciudad: el camino parece despejado. Me sorprende un abismo que [20] detiene mi camino. Me detengo. Imposible saltarlo.

Veo que a un costado hay maderas, clavos y herramientas. Me doy cuenta de que está allí para construir un puente. Nunca he sido hábil con mis manos… Pienso en renunciar. Miro la meta que deseo… y resisto.

Empiezo a construir el puente. Pasan horas, o días, o meses. El puente está hecho.

[25] Emocionado, lo cruzo. Y al llegar al otro lado… descubro el muro. Un gigantesco muro

frío y húmedo rodea la ciudad de mis sueños…

Me siento abatido… Busco la manera de esquivarlo. No hay caso. Debo escalarlo. La ciudad está tan cerca… No dejaré que el muro impida mi paso.

Me propongo trepar. Descanso unos minutos y tomo aire… De pronto veo, a un costado [30] del camino un niño que me mira como si me conociera. Me sonríe con complicidad.

Me recuerda a mí mismo… cuando era niño.

Quizás por eso, me animo a expresar en voz alta mi queja: -¿Por qué tantos obstáculos entre mi objetivo y yo?

El niño se encoge de hombros y me contesta: -¿Por qué me lo preguntas a mí?

[35] Los obstáculos no estaban antes de que tú llegaras… Los obstáculos los trajiste tú.

Jorge Bucay.

www.rincondelplaneta.com.ar

Acceso en: 30/03/2014.

De acuerdo con el Texto 1, marque las proposiciones verdaderas (V) o falsas (F).

( ) La palabra “distinguirla” (línea 4) podría ser reemplazada sin cambiar el sentido de la frase por “la distinguir”.

( ) La palabra “hacia” (línea 11) representa el verbo hacer en pretérito imperfecto del indicativo.

( ) La palabra “hace” (línea 12) representa el verbo hacer en presente del indicativo.

( ) El pronombre “la” (línea 16) que acompaña al verbo pasar se está refiriendo a la meta.

( ) El pronombre “la” (línea 16) que acompaña al verbo pasar se está refiriendo a la zanja.

Ahora señale la alternativa que tiene la secuencia correcta, de arriba hacia abajo.

Questão 64857

UFRR

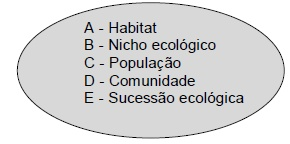

(UFRR 2014) Correlacione conceitos e termos. Em seguida assinale a alternativa que contém a sequência correta.

1. Processo gradativo de colonização de um ambiente, com alterações na composição das comunidades ao longo do tempo.

2. Conjunto de populações de diferentes espécies que vivem numa mesma região.

3. Conjunto de relações e de atividades características da espécie, no local onde ela vive.

4. Todos os indivíduos de uma mesma espécie que habitam um determinado local num determinado momento.

5. Ambiente em que vive determinada espécie, caracterizado por suas propriedades físicas e bióticas.

Questão 64858

UCS

A sucessão ecológica é o processo de colonização de um ambiente por seres vivos. Com o passar dos anos, os organismos que habitam um determinado local vão sendo substituídos por outros. São exemplos de espécies pioneiras em um processo de sucessão ecológica na superfície de uma rocha:

Ver questão